An Analysis of Sir Ken Robinson’s Education Philosophy

In his legendary 2006 TED Talk, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?”, Sir Ken Robinson argued that creativity is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status. Yet, he famously claimed that we are running national education systems where mistakes are the worst thing you can make, resulting in a system that educates people out of their creative capacities rather than into them.

Here is a breakdown of why Robinson believed our school systems are fundamentally designed to suppress the very innovation we now need.

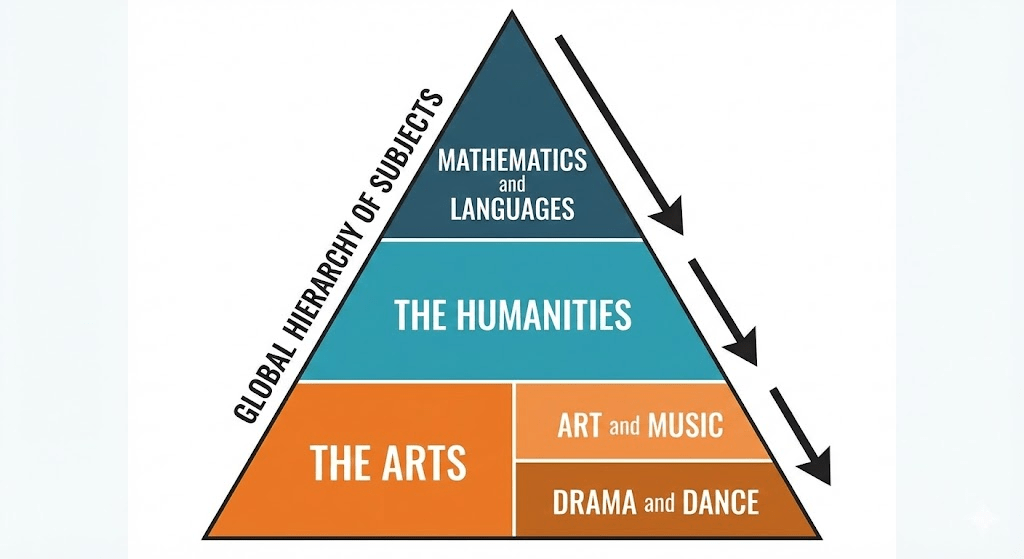

1. The Global Hierarchy of Subjects

Robinson observed that every education system on Earth shares the same rigid hierarchy of subjects. No matter where you go, the structure remains consistent:

- Mathematics and Languages (At the top)

- The Humanities (In the middle)

- The Arts (At the bottom)

Even within the arts, there is a further hierarchy: Art and Music are generally given higher status than Drama and Dance. Robinson noted, “There isn’t an education system on the planet that teaches dance every day to children the way we teach them mathematics.”

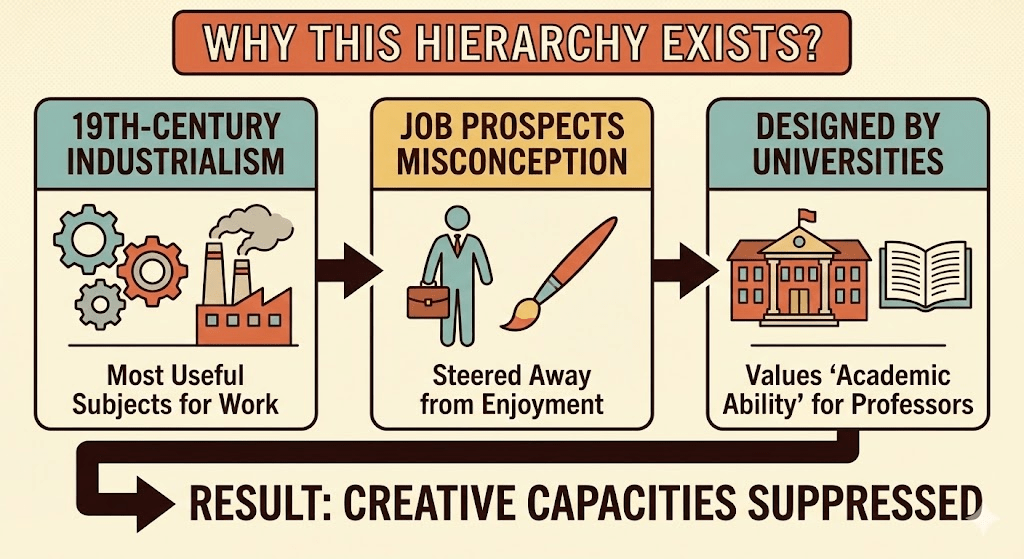

Why does this exist?

This hierarchy is not accidental; it is rooted in 19th-century industrialism. The most useful subjects for work were placed at the top. As a result, millions of students are steered away from things they enjoy (like art or music) on the benign but mistaken grounds that they will never get a job doing them. This system values “academic ability” above all else because it was designed by universities to create university professors.

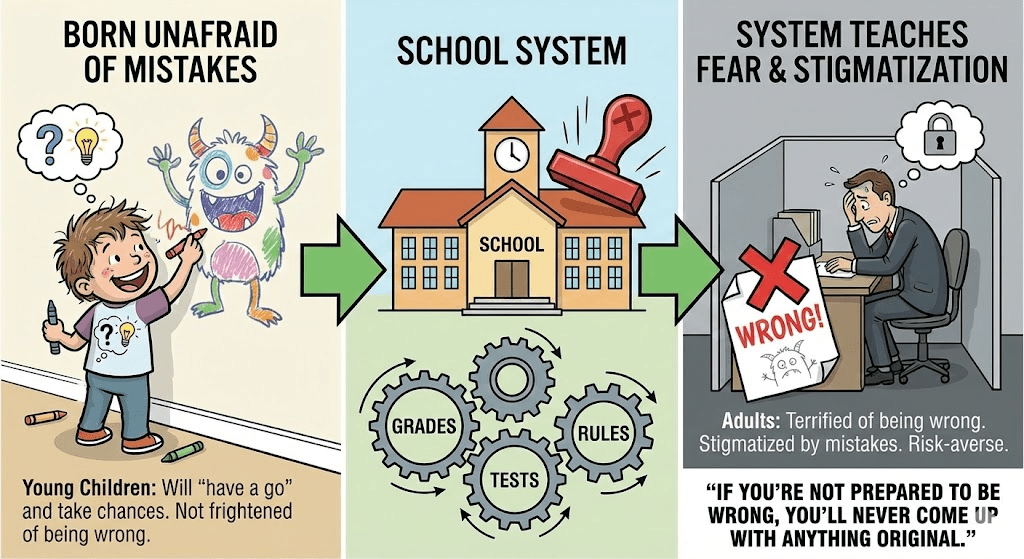

2. The Stigmatization of Mistakes

One of Robinson’s central arguments was the relationship between creativity and the fear of failure.

- Children are born unafraid: Young children will take a chance. If they don’t know the answer, they’ll “have a go.” They are not frightened of being wrong.

- The system teaches fear: As children move through school, they learn that mistakes are stigmatized. By the time they become adults, they are terrified of being wrong.

Robinson argued, “If you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original.” By stigmatizing mistakes, schools kill the willingness to take the risks necessary for innovation.

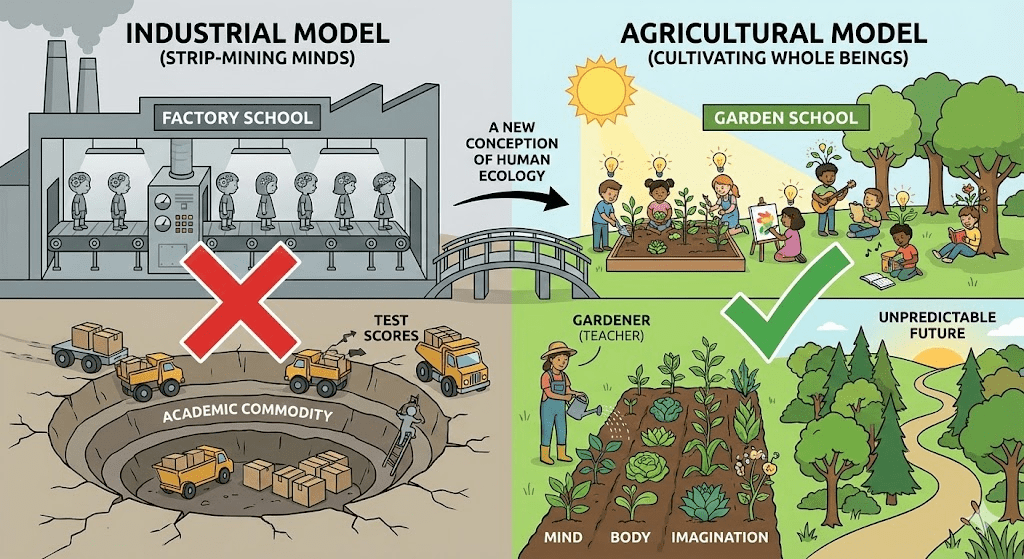

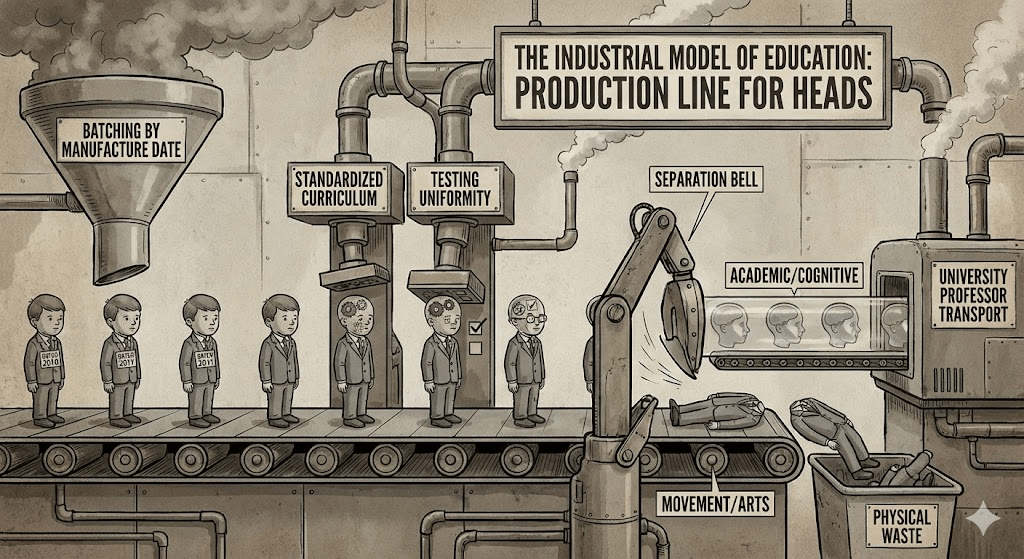

3. The Industrial Model of Education

Our current system creates a “production line” mentality. Robinson pointed out that schools are organized like factories:

- Batching: Students are educated in “batches” based strictly on age, as if the most important thing about them is their “date of manufacture.”

- Standardization: Curricula and testing are standardized, ignoring the fact that learning is organic and individual.

- Separation: The day is broken into distinct bells and separate subjects, disconnecting the body (movement/arts) from the mind (academic/cognitive).

This “disembodied” education treats students—especially university professors—as if their bodies are merely transport mechanisms for their heads.

4. The Story of Gillian Lynne

To illustrate the tragedy of lost potential, Robinson told the true story of Gillian Lynne.

As a child in the 1930s, Gillian was performing poorly in school. She couldn’t sit still, was fidgety, and disrupted class. The school wrote to her parents believing she had a learning disorder. Her mother took her to a specialist.

After listening to the mother’s concerns, the doctor turned on the radio and left Gillian alone in the room, watching her from the hallway. Gillian immediately began to move to the music. The doctor turned to her mother and said:

“Mrs. Lynne, Gillian isn’t sick. She’s a dancer. Take her to a dance school.”

She did. Gillian went on to become a soloist at the Royal Ballet and later choreographed some of the most successful musical theater productions in history, including Cats and The Phantom of the Opera.

The Lesson: Another doctor might have put her on medication and told her to calm down. The system was designed to suppress her natural talent because it didn’t fit the “academic” mold.

Conclusion: A New Conception of Human Ecology

Robinson concluded that we must move from an industrial model of education to an agricultural one. We cannot make a plant grow; we can only provide the conditions under which it will flourish. Similarly, schools must stop strip-mining the minds of children for a specific commodity (academic ability) and start cultivating their whole beings—mind, body, and imagination—to prepare them for an unpredictable future.